It might be hard to believe, but the SSL/TLS Ecosystem is nearly 20 years old. It’s time to take stock and see how we’re doing with regards to TLS certificates. In this article, we’ll primarily discuss certificates themselves and not web server configuration, although that is often a source of problems.

In the last few years, we’ve endured three major certificate-based migrations:

- Away from the MD2 and MD5 hash algorithms to SHA-1

- Away from small RSA keys to 2048-bit keys or larger

- Away from the SHA-1 hash algorithm to SHA-256

What’s driving these migrations? Primarily, it’s the relentless march of attacks. As Bruce Schneier says, “Attacks always get better; they never get worse.” To stay ahead of these attacks, Certification Authorities and browser vendors joined together several years ago to form the CA/Browser Forum, and published several requirements documents: the Baseline Requirements, the EV SSL Guidelines and the EV Code Signing Requirements.

What’s slowing these migrations? Primarily, it’s the use of of SSL/TLS in non-browser applications. These include mail, XMPP and other non-web servers, Point-of-Sale (POS) and other devices. These applications and devices lack the auto-update capabilities that were developed by web browser vendors. In addition, there’s considerable institutional inertia. Your average server machine is not frequently updated (except perhaps for OS security patches). Companies wait years to perform a server or even application refresh, because they’re busy with more important things. A common attitude is “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

The Good

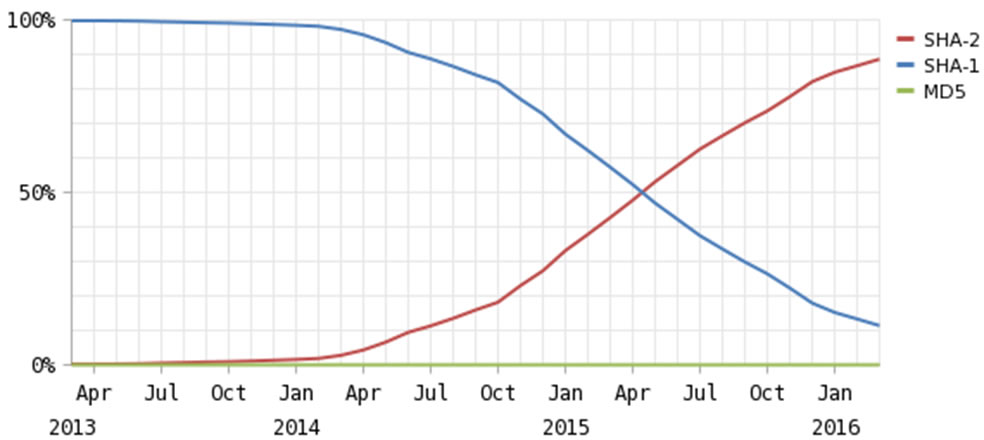

But the industry can take credit for a number of positive developments. First, the trajectory of SHA-2 deployment is encouraging (graph courtesy of Netcraft):

Small key sizes have been largely eliminated. A recent Netcraft study found that 99.98% of web certificates contain RSA 2048-bit, ECC 224-bit or larger keys. In fact, over 200,000 certificates on the web have RSA keys of greater than or equal to 4096 bits!

Thanks to the CA/Browser Forum efforts to create workable standards around certificate profiles, there’s now a lot more consistency in web-based certificates than there was even a few years ago. The creation of the Extended Validation (EV) standard raised the bar on strong authentication, and now over 10% of certificates seen on the Internet are EV (according to the Trustworthy Internet Movement or TIM).

The Bad

However, the situation isn’t all good. Although we’ve made great strides towards deployment of SHA-2 certificates, 10-11% of all certificates seen on the web still use SHA-1 (Netcraft and TIM). Browsers continue to work fine with SHA-1 certificates, and won’t display any errors unless the certificate expires after 31 December 2016.

We know that some customers are having difficulty upgrading systems and applications to support SHA-2. For example, Netcraft reported that the US Department of Defense (DOD) is still issuing SHA-1 certificates.

And despite a huge effort to replace TLS certificates that contain keys deemed too small to be secure, Netcraft found more than 1,000 with RSA keys smaller than 2048 bits, or ECC keys smaller than 224 bits.

Browser vendors have begun to add certain compliance checks, so they may display an error when they encounter a TLS certificate that violates one or more requirements that they deem critical. When Netcraft surveyed TLS certificates on the web, they found that around ~6% of all EV certificates violated one or more requirements in the CA/Browser Forum’s EV Guidelines. To be sure, most of these violations are unlikely to cause usability problems, for example, some are missing a valid Subject Business Category. The certificate will function properly, but it provides somewhat less information to relying parties.

Netcraft also discovered that around 3% of all non-EV TLS certificates violated one or more requirements in the CA/Browser Forum’s Baseline Requirements. Again, most are policy violations (CN must appear in SAN, invalid Subject State or Country, etc.) that are unlikely to cause usability problems

A small number of web sites were seen with certificate chains in which strong (large) keys were signed by weaker (smaller) keys. Again, these will function properly, but they don’t necessarily provide the cryptographic protection expected by the certificate owner (a certificate chain, like a physical chain, is only as strong as its weakest link). Examples include ECC 384-bit keys signed by ECC 256-bit keys, ECC 384-bit keys signed by RSA 2048-bit keys, and RSA 4096-bit and 8192-bit keys signed by RSA 2048-bit keys.

Certificate expiration is embarrassing, but companies large and small still fail to renew certificates on time. Although there are many tools to help customers inventory and keep track of their certificates, this problem persists, perhaps due to the failure of browsers to check the status of most certificates.

The Ugly

Recent Netcraft surveys found some truly surprising certificates on the Internet. Approximately two-thirds of all TLS certificates seen are valid, and issued by a trusted CA. The remaining one-third are either self-signed, expired, signed by an unknown issuer or contain mismatched names. Since all major browsers display errors in all these cases, it’s likely that these certificates are used in server-to-server or other non-browser applications.

Although the MD5 hash algorithm was deprecated eight years ago, one MD5, three-year certificate was found on the Internet. It was issued in 2013 by a public CA with an RSA 1024-bit key. It violates six other Baseline Requirements. And one certificate containing a 512-bit RSA key, used by Government of South Korea was found. Although it’s signed using SHA-2, it’s got four other Baseline Requirements violations.

One certificate was found with an RSA exponent of one. Since RSA encryption involves raising an exponent to a certain power, an exponent of one means that no encryption occurs, and TLS data is sent in cleartext.

Multiple Common Names (CNs) are prohibited, but Netcraft found certificates with up to 24 CNs. A 2009 study demonstrated attacks on certificates with multiple CNs, yet they persist.

One certificate with an RSA 15,424-bit key was found on the Internet! (It also includes 72 SAN values, almost a record!) It’s an Apache server, but not a web site, so it’s not used with browsers. Perhaps it’s being used to test the performance of servers with very large public keys. But it certainly causes no harm to the Web.

Some ten-year end-entity certificates appear on the Internet, issued after the BRs became effective (hence violating the BRs). Most browsers block access to sites with public TLS certificates with excessive dates, so it’s likely that these sites are not used with browsers.

Certificates containing more than 50 subjectAlternativeNames (SANs) were found in the survey. Although there is nothing illegal about such certificates, the presence of so many SANs makes the certificate significantly larger, and might cause performance problems.

What’s Acceptable?

How do you insure that your certificates are strong enough for today’s attackers and compliant with best practices? Here are some guidelines:

A certificate with a 2048-bit RSA key, signed with the SHA-256 hash algorithm is adequate for now. Keep SANs to a minimum (20 or fewer), and make sure your CA puts only one Common Name in the certificate.

Replace all weak, invalid, revoked or soon-to-expire certificates. Generate a new key pair every time you replace a certificate.

Test your certificate and web server configuration with all major browsers (don’t forget mobile browsers, which often behave differently from their desktop counterparts).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Netcraft, the International Computer Science Institute and the Trustworthy Internet Movement (TIM) SSL Pulse for information used in this article.